It affects women more frequently, particularly after the age of 50. Its progression is unpredictable: some forms remain stable, while others intensify over time, requiring accurate diagnosis and personalized care.

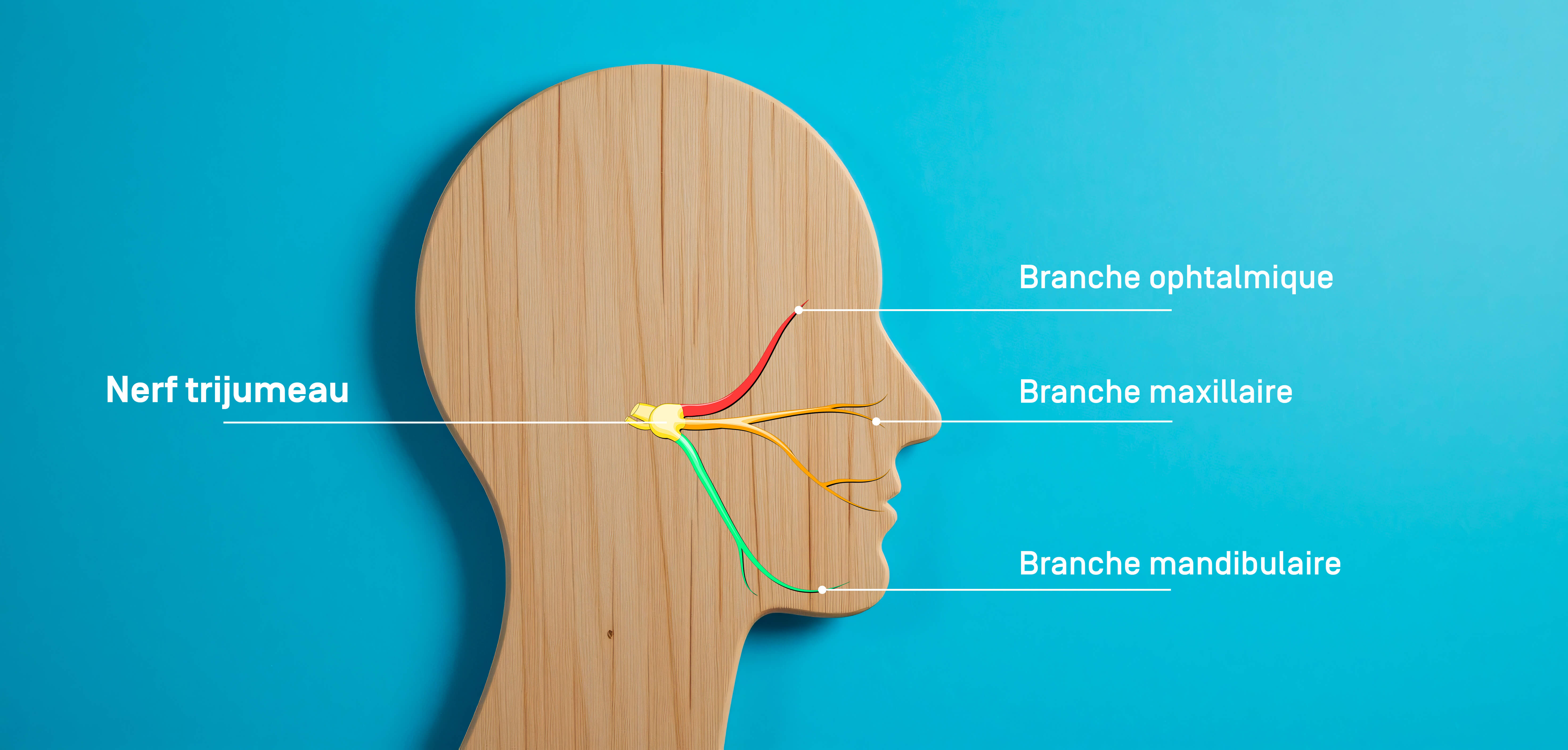

Anatomy of the trigeminal nerve

The trigeminal nerve (or cranial nerve V) is the largest of the cranial nerves. There is a trigeminal nerve on the left and right sides, each providing innervation to half of the face, controlling skin sensitivity, the mucous membranes of the mouth and nose, and the motor function of the masticatory muscles.

This nerve divides into three main branches:

- V1 (ophthalmic): provides sensitivity to the forehead, the cornea of the eye, and the upper part of the face (particularly the forehead).

- V2 (maxillary): provides sensitivity to the cheek, upper lip, upper teeth, and wing of the nose.

- V3 (mandibular): provides sensitivity to the lower jaw, lower lip, lower teeth, and innervation of the masticatory muscles.

Symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia

The main symptom of trigeminal neuralgia is sudden, brief, and extremely intense facial pain on one side of the face, described as feeling like an electric shock, burning, sharp stinging, or a “stabbing” sensation. It lasts from a few seconds to two minutes, with refractory periods between attacks.

This pain is typically triggered by everyday activities such as washing your face, brushing your teeth, talking, eating, or even a light breeze. In some cases, a dull, continuous pain persists between attacks.

The pain most often affects the V2 and V3 branches. Involvement of the V1 branch is rarer. Neuralgia is usually unilateral, but in rare cases, it can affect both sides of the face alternately.

Without treatment, attacks can become more frequent, more intense, and debilitating, impacting the patient's quality of life.

Causes of trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia can be classified into three main forms: primary (or essential), secondary, and idiopathic. Each form has a distinct origin, which may or may not be identified.

In most cases, it is primary neuralgia, caused by compression of the trigeminal nerve at its root, where it enters the brainstem. This compression is often caused by a loop in a blood vessel, usually the superior cerebellar artery. This continuous pressure on the nerve alters its structure, in particular by damaging the myelin sheath, a kind of natural insulator that surrounds the nerve fibers. This phenomenon is called demyelination.

Myelin plays an essential role: it allows electrical signals to travel correctly and quickly along the nerve. When it is damaged or destroyed, the transmission of these signals becomes chaotic. The nerve can then send inappropriate pain signals, even in the absence of any real harmful stimulus. It is this dysfunction that causes the sudden, intense pain characteristic of trigeminal neuralgia.

However, it should be noted that the presence of a vascular loop in contact with the trigeminal nerve is not uncommon and does not necessarily lead to trigeminal neuralgia.

The secondary form is associated with underlying conditions such as multiple sclerosis, posterior fossa tumors (such as meningiomas, acoustic neuromas, or epidermoid tumors), or arteriovenous malformations, which can put pressure on the nerve.

Finally, the idiopathic form refers to cases in which no causal factor can be identified despite thorough examination. It may be linked to genetic susceptibility or central sensitization mechanisms.

Risk factors for trigeminal neuralgia

Certain profiles seem to be more prone to trigeminal neuralgia. Age is one of the first factors to consider: the majority of cases are diagnosed after the age of 50, although earlier forms do exist. The prevalence of this condition is twice as high in women as in men.

There may be a family history of the condition, suggesting a possible role for genetic factors. The presence of certain neurological disorders, particularly multiple sclerosis, significantly increases the risk, especially when the neuralgia is bilateral.

Finally, more general factors such as high blood pressure, smoking, or chronic stress are also suspected of increasing the risk of developing this condition

Diagnosing trigeminal neuralgia

The diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is based primarily on a thorough clinical analysis to assess the characteristic type of pain (brief, electric, very intense, triggered by a mild stimulus), its location (in the trigeminal nerve area, in one or more of its branches), its frequency, and the triggering factors.

The neurological examination is generally normal. However, sensory or motor deficits should raise suspicion of a potential secondary cause.

In addition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is most often requested to rule out a tumor or multiple sclerosis. MRI also allows visualization of possible vascular compression of the nerve.

Treating trigeminal neuralgia

The treatment of trigeminal neuralgia is based on a gradual approach: pharmacological treatment as a first-line therapy, followed by interventional treatment for refractory forms. The aim is to restore an acceptable quality of life by controlling painful attacks while limiting adverse effects.

Drug treatments

Antiepileptic drugs are the first-line treatments. They are effective in 70 to 90% of cases. These molecules work by stabilizing nerve transmission within the trigeminal nerve. Treatment always starts at a low dose, which is then gradually increased depending on the clinical response and the patient's tolerance. This slow titration helps to limit side effects—drowsiness, nausea, cognitive impairment—which can limit long-term use.

Depending on the dose required and the therapeutic response (effectiveness and/or side effects), different medications may be offered, either alone or in combination.

When medications become ineffective or poorly tolerated, several interventional options are available to patients

Neurosurgery and minimally invasive procedures

- Microvascular decompression (MVD) involves removing the vessel compressing the nerve by inserting a cushion. It is considered the only method capable of eliminating the anatomical cause of pain in cases of primary neuralgia. Its effectiveness can exceed 80% with lasting results, but it requires general anesthesia and cranial surgery with trepanation, with the risks associated with the latter. It is generally reserved for relatively young patients with vascular compression confirmed by MRI.

- Percutaneous ablative techniques, such as thermal rhizotomy, balloon compression, or glycerol injection, aim to selectively damage the pain fibers at the Gasser ganglion (the area where the trigeminal nerve root divides into its three branches). They are performed by minimally invasive puncture through an opening in the skull bone at the cheek level. They are indicated in elderly or frail patients and can provide rapid pain relief, but they often result in lasting sensory disturbances.

Radiosurgery

Stereotactic radiosurgery represents a major advance in the treatment of nervous system disorders, including trigeminal neuralgia. For the latter, it involves focusing a very small beam of radiation with high precision on the intracranial root of the trigeminal nerve. The procedure is non-invasive and does not require general anesthesia or hospitalization. It provides gradual relief in the weeks or months following treatment, with very few risks of side effects and excellent tolerance. This technique is therefore particularly indicated as a first-line treatment in cases where medication is no longer effective and in patients who cannot undergo invasive surgery. Clinical results show an improvement in pain in 70 to 90% of patients, with an average delay of 6 weeks to 2 months. Long-term recurrence is possible but can be treated with a second irradiation. Its advantages include no incision, a quick return home, and a favorable safety profile.

Progression and possible complications

Trigeminal neuralgia often follows a flare-up pattern, with periods of spontaneous remission. However, without treatment, attacks can become more frequent, longer, and more intense, having a lasting impact on daily life.

Some forms progress to constant pain that is difficult to control. Weight loss, depression, or anxiety secondary to chronic pain may occur if the condition is poorly managed.

Interventional treatments, although generally effective, are not without complications. Microvascular decompression surgery can cause damage to the cranial nerves and carries the risks inherent in any neurosurgical procedure (healing problems, hematoma, infection, fistula) and general anesthesia. Ablative procedures can cause hypoesthesia, painful anesthesia (pain in an insensitive area), or, more rarely, persistent post-surgical neuralgia. Finally, in the case of stereotactic radiosurgery, complications are rare and most often reversible, limited to changes in facial sensitivity on the treated side (facial hypoesthesia, paresthesia).

When should you contact the Doctor?

Any sudden, unilateral facial pain that feels like an electric shock or burning sensation, especially if it is triggered by simple everyday movements, should be cause for concern. It is recommended to seek medical advice promptly if:

- the pain is recurrent or severe,

- it is accompanied by neurological symptoms (speech disorders, facial weakness),

- conventional pain relief treatments are not effective.

Early diagnosis can prevent frequent medical consultations and ensure rapid access to appropriate treatment.

Care at Hôpital de La Tour

At Hôpital de La Tour, the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia is based on a highly specialized and multidisciplinary approach, provided by experts in neurology, functional neurosurgery, and radiosurgery. Each patient benefits from a personalized and structured care pathway, from initial diagnosis to the evaluation of the most appropriate treatment options. Specialized anesthesiologists also participate in the management of these facial pains at the Pain Clinic.

The Pain Clinic

The Pain Clinic at Hôpital de La Tour works in conjunction with other disciplines to support patients with chronic pain, particularly those with refractory forms or awaiting neurosurgical treatment.

The team offers:

- specialized medication management (antiepileptics, coanalgesics, IV infusions of lidocaine, magnesium, or ketamine, topical treatments),

- targeted infiltrations at the branches of the trigeminal nerve,

- neuromodulation techniques (pulsed radiofrequency, neurolysis, or percutaneous ablative techniques, neurostimulation, etc.) not only of the Gasserian ganglion, but also of the distal branches (V1, V2, V3) depending on the topography of the pain

- multidisciplinary support including psychological support, hypnosis, TENS, and therapeutic education.

The goal is to offer an individualized approach focused on pain relief and improving quality of life, while working closely with the neurology, neurosurgery, and radiosurgery teams.

The NeuroKnife Center

The NeuroKnife Center, which specializes in stereotactic radiosurgery of the nervous system, offers a non-invasive alternative to traditional neurosurgical procedures. Its latest-generation linear accelerator adapts the radiation beam to the morphology of the trigeminal nerve in real time, without the need for a rigid frame. It enables targeted, precise, and safe treatment. This technique provides lasting pain relief in the majority of cases, with increased comfort for the patient and little risk of side effects.